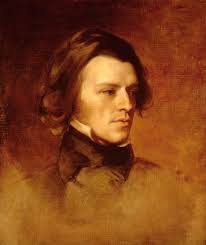

Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892) is often thought of as the quintessential Victorian poet: solemn, moral, deeply religious (or spiritually conflicted), and a poetic voice enshrined in the nation’s imagination. But behind that public persona lies a more turbulent, restless, and fascinating inner life — one that has lately received renewed attention from biographers and literary historians.

In 2025, Richard Holmes published The Boundless Deep: Young Tennyson, Science and the Crisis of Belief, which re-casts Tennyson’s early years through the lens of scientific upheaval, existential anxiety, and emotional intensity. In doing so, Holmes teases out lesser-known details and contradictions that complicate the familiar myth of the Victorian laureate.

Early Life: Roots, Family Shadows, and an Unsettling Household

Lineage and Upbringing

Tennyson was born on August 6, 1809, in Somersby, Lincolnshire, the fourth of twelve children (though not all survived) of George Clayton Tennyson, the rector of Somersby, and Elizabeth Fytche. George Tennyson was a capable scholar: he taught his sons Greek, Latin, and encouraged a range of reading. But he was also afflicted by mental instability and alcoholism, and eventually the home descended into emotional violence and dysfunction.

One harrowing anecdote: Holmes (in his new biography) revisits a family tradition that the rectory cook died in a fire — reputedly her dress caught alight in the kitchen. Details remain obscure, but it is often cited as a traumatic event in the household’s memory.

By the 1820s, George’s condition deteriorated: mood swings, episodes of violence, and public humiliations became more frequent. Holmes writes that at one point George allegedly stormed around the house with a loaded gun and knife, threatening to stab his son Frederick. Although the veracity is debated, it reflects how haunted the family memory was.

The siblings each bore different burdens: one brother spent decades in a lunatic asylum; another became addicted to opium; another descended into alcoholism. Tennyson himself sometimes described his family as of a “black-blooded race,” meaning prone to melancholy and inner tumult.

Early Literary Impulses

Even as a boy, Tennyson was precocious. At age 12 he composed a 6,000-line epic (though it is fragmentary and not extant in full). By his teens he was imitating Pope, Milton, Scott and internalizing a wide range of poetic idioms.

His formal schooling was uneven: he attended King Edward VI Grammar School in Louth for a few years, but left in 1820 and much of his education was home-tutored by his father. He entered Trinity College, Cambridge in 1827 (alongside brothers Frederick and Charles) but did not complete a degree.

It was at Cambridge that one of the most defining friendships of his life was forged: with Arthur Henry Hallam. Hallam, the son of historian Henry Hallam, became Tennyson’s closest friend and intellectual mirror. Tennyson also joined the Cambridge Apostles, a secret society of intellectuals, many of whom would become prominent in Victorian letters.

The young Tennyson also immersed himself in the scientific currents of the day: Holmes shows how he studied microscopic life, observed the moon, read popular works of geology and astronomy, and grappled with the emerging ideas of deep time and species change, all while feeling them as existential threats.

Spells of melancholy haunted him: he sometimes wrote of “confusions of a wasted youth,” of feeling the smallness and emptiness of life envelop him. One poem, The Two Voices, dramatizes an inner dialogue between a suicidal impulse and a countering voice of hope, emblematic of the inner crisis Tennyson wrestled with.

When he began publishing, he was cautious: his first volume, Poems, Chiefly Lyrical, appeared in 1830; a second, in 1832, drew harsh criticisms, particularly for perceived affectation and obscurity, which bruised his confidence. In 1842 he reissued and heavily revised earlier poems in Poems (1842) to address those critiques and solidify his reputation.

Middle Years: Tragedy, Laureateship, and Poetic Immortality

The Death of Hallam & In Memoriam

Arthur Hallam’s sudden death in 1833 (from a cerebral hemorrhage) struck Tennyson to the core. The grief haunted him for decades, culminating in In Memoriam A.H.H. (published in 1850). This long elegiac sequence grapples with faith, doubt, loss, time, and the void left by a vanished friend. The line “’Tis better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all” is among his most famous.

Holmes suggests that In Memoriam also internalizes the spiritual crisis triggered by advancing geology, astronomy, and challenges to traditional Christian cosmology. The tension between scientific progress (deep time, extinction, non-anthropocentric universe) and Christian consolation was one Tennyson never resolved.

Poet Laureate & Public Life

After the death of William Wordsworth in 1850, Tennyson was appointed Poet Laureate on November 5, 1850 — a post he held till his death in 1892. The appointment came partly due to In Memoriam’s success and through the advocacy of Prince Albert.

Being laureate meant composing occasional poems for national events, births, funerals, royal anniversaries. Some viewed the role as stifling, others as a platform. Over time, Tennyson evolved into a sort of national poet — the voice to which many turned in times of mourning or celebration.

His reputation and influence grew. He was offered honorary doctorates from Oxford and Edinburgh; Cambridge invited him three times (he declined). Among his circle were luminaries like Thomas Carlyle (with whom he could drop in unannounced), and he kept correspondences with writers, scientists, and thinkers of the age.

At court, Queen Victoria reportedly found comfort in In Memoriam after Prince Albert’s death; she once remarked that “next to the Bible, In Memoriam has been my comfort.” In a diary entry, she initially described Tennyson on first meeting as “peculiar looking” and “oddly dressed”—but later came to admire him personally.

Marriage, Family, and Domestic Life

Perhaps less well known: Tennyson’s marriage to Emily Sellwood was delayed by financial insecurity and concerns about his health (particularly fears he might inherit epilepsy from his father). They finally married on June 13, 1850 — shortly after he accepted the laureateship.

Emily played a much larger role than is often acknowledged: she was his business manager, proofreader, hostess, manager of household affairs, gatekeeper of visitors, and emotional anchor. They had two surviving sons (Hallam and Lionel). Their first child was stillborn, a tragedy Tennyson later reflected upon in private verse.

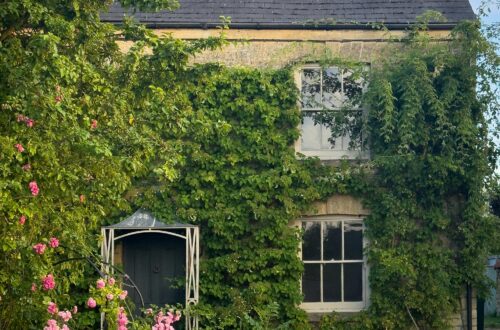

Years in Freshwater, Isle of Wight (at Farringford House) became their primary retreat, though visitors often overflowed. Emily, as hostess, sometimes lamented that the house felt more like an inn than a home.

Major Works & Themes

Tennyson’s poetic output is vast. Some highlights and thematic patterns:

• Poems (1842) established his mature voice; included “The Lady of Shalott,” “Mariana,” “Ulysses,” “Locksley Hall,” “Break, Break, Break.”

• The Princess (1847) is a serio-comic blank verse narrative that explores women’s education and gender roles; it later inspired Gilbert & Sullivan’s Princess Ida.

• Idylls of the King, his Arthurian cycle, blended myth, morality, and allegory in extended narrative verse.

• Shorter lyrics such as “Tears, Idle Tears,” “Break, Break, Break,” “Crossing the Bar,” “The Lotos-Eaters” showcase his mastery of sound, mood, and elegiac tone.

One of the striking features of Tennyson’s craft is his metrical and sonic experimentation — he was often attentive to internal music, alliteration, subtle enjambment, and the rhythmical pacing of narrative.

Even in his more reputedly staid works, one can trace the anxiety, the cosmic disquiet, and the haunted edges of doubt that he carried from his youth.

Late Years, Legacy, and Obscurities

The Voice from the Past: Edison’s Wax Cylinders

One of the most enthralling bits of biographical lore: late in life, Tennyson was recorded reciting “The Charge of the Light Brigade” onto a wax cylinder by agents of Thomas Edison (circa 1890). This is one of the few surviving audio artifacts of a Victorian poet’s voice.

The recording is fragmentary, affected by static, and parts are difficult to interpret. But some scholars have pointed out a curious “knocking” noise audible about 90 seconds in. Some have speculated Tennyson himself may have simulated the sound of horses’ hooves to evoke the cavalry charge. The recording remains a haunting window into the past — a poet’s voice from the Victorian dusk.

Interestingly, Edison reportedly made about 30 such cylinders of Tennyson’s voice, but due to poor preservation (some stored near radiators, attacked by mold), only about seven remain.

Reputation, Decline, and Revival

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Tennyson’s reputation was somewhat ambivalent. Critics accused him of Victorian pomposity, of overstatement, and of moral moralizing. Yet his formal mastery and emotional depth continued to be admired.

In the mid-20th century, modernist critics sometimes dismissed his work as sentimental, but later scholars recovered his significance as a voice through which Victorian anxiety, scientific upheaval, and spiritual conflict were negotiated.

Holmes’s recent reassessment nudges us to see a younger Tennyson not as an embarrassingly stiff relic but as a restless, questioning, intellectually alive poet wrestling with a new age.

Other Obscurities & Anecdotes

• Clichés That Live On. Many lines from Tennyson have become commonplace clichés — “’Tis better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all”, “Theirs not to reason why, / Theirs but to do and die” — often stripped of their original context.

• Modest Diplomas. Though Oxford and Edinburgh awarded him honorary degrees, Cambridge invited him multiple times, and he modestly declined.

• A Bohemian Wardrobe. Holmes notes Tennyson’s personal style in youth was eccentric: he sometimes wore a long Spanish cloak, broad hat, smoked heavily, and cultivated a scruffy charisma.

• Restless Travel. In his younger years he made spontaneous travels — Amsterdam, Paris, Calais — often telling friends he might leave mid-evening for some unknown place. Holmes frames this restlessness as a symptom of existential dislocation.

• Science and Spiritual Anxiety. He was drawn to microscopes, telescopes, astronomy, geological thinking, and the works of thinkers like William Whewell, Charles Lyell, Mary Somerville, Charles Babbage. These ideas haunted him.

• Aesthetic Revisions. Tennyson often revisited and heavily revised earlier poems. Poems (1842) is in part a reworking of his 1830/1832 material, shaped by critics’ responses.

• Cross-cultural Legacy. His poems inspired later cultural works: The Princess influenced Princess Ida (Gilbert & Sullivan). His lines appear even in unexpected places: e.g. “The Charge of the Light Brigade” was referenced in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine.

Final Years & Death

In his later years, Tennyson’s output slowed, but he remained a towering figure. He accepted a peerage in 1884 (becoming Baron Tennyson of Aldworth and Freshwater). He died on October 6, 1892, at Aldworth, Surrey, and is buried in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey.

Emily outlived him by a few years, dying in 1896; she is buried on the Isle of Wight.

Reflections: Why Tennyson Still Matters (and What to Emphasize in a Blog)

1. Dualities & Tensions. Tennyson’s inner life was marked by tension: doubt and faith, scientific awe and spiritual longing, melancholic inertia and drive. These contradictions make him a rich subject, not a static monument.

2. Science as Poetic Fuel — and Threat. Tennyson’s engagement with 19th-century science (geology, astronomy, biology) is not a side note but a central strain in his work. His poetry often reads as a response to the cosmos, to extinction, to the silence beyond humankind. Holmes’s recent work foregrounds this interplay.

3. The Voice — Alive, Distorted, Haunting. The Edison cylinders remind us that Tennyson was not just a name but a speaking presence. The crackle and the knocking make him distant and uncanny.

4. Revision, Self-Fashioning, and Evolving Legacy.Tennyson was self-conscious, rewrote his past, cultivated persona, and responded to criticism. He was not a fixed “Victorian master,” but someone who grew, adapted, and often doubted.

5. Cultural Afterlives. Whether in operas, quotations, references in film or music, Tennyson’s influence continues. Bringing those connections into a blog can show how a 19th-century poet still lives in unexpected ways.

6. Unearthing the Obscure. Stories like the cook’s tragic death, his father brandishing weapons, the lost wax cylinders, the brooding youth name-dropping travels — such details humanize the great name. They invite readers to see Tennyson not as an icon, but a man haunted by time, possibility, and loss.

Thanks for reading. To read more of my posts, head to rkartandesign.com

To read my short stories, head to storytimebyrk.com

🌿 Recommended Reading

1. The Boundless Deep — Richard Holmes (2025)

A luminous modern biography uncovering Tennyson’s turbulent youth, fascination with science, and inner battles of faith.

2. In Memoriam A.H.H. — Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Tennyson’s great elegy for his friend Arthur Hallam — a cornerstone of Victorian poetry wrestling with grief and belief.

3. Five Facts About Alfred, Lord Tennyson — Bookstellyouwhy.com

A fascinating, informal look at the man behind the poetry — from his eccentric habits to Queen Victoria’s admiration.

4. Voices from the 19th Century — Open Culture

Hear Tennyson’s actual voice reciting “The Charge of the Light Brigade”on Edison’s wax cylinders — one of the earliest literary recordings.

5. Engelsberg Ideas: “Tennyson Was Young Once”

A haunting exploration of the poet’s dark family history, his melancholy genius, and the demons that shaped his art.

6. Historic UK: Alfred, Lord Tennyson

An overview of Tennyson’s life and times, including his relationship with Queen Victoria and rise to national fame.