When readers think of the Brontë name, they often recall the tempestuous genius of Emily Brontë or the passionate intensity of Charlotte Brontë. Yet within this extraordinary literary family, Anne Brontë stands as perhaps the most quietly revolutionary voice of them all.

Her novels were not written to shock with gothic excess or romantic turbulence. Instead, Anne wrote with moral precision, psychological realism, and a steady commitment to truth—especially the truth about women’s lives in the nineteenth century.

Early Life in Haworth

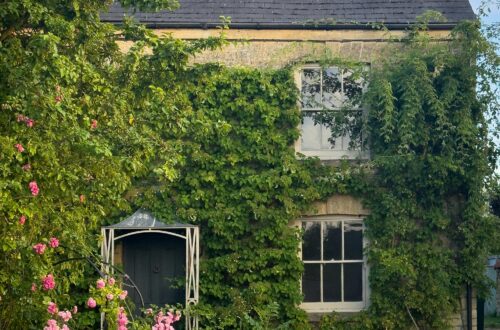

Anne was born on January 17, 1820, in the small Yorkshire village of Thornton and grew up in the remote parsonage at Haworth. Her father, Patrick Brontë, was a clergyman of Irish descent, and her mother, Maria Branwell, died when Anne was just a year old.

The Brontë children—Charlotte, Emily, Anne, and their brother Branwell—developed an intensely imaginative inner world. They created elaborate fictional kingdoms, including Angria and Gondal, writing miniature books filled with poetry, political intrigue, and romantic drama.

While Charlotte and Emily often receive credit for the dramatic scope of these juvenilia, Anne’s contributions reveal early evidence of her clarity and moral seriousness.

The Governess Experience: Writing from Lived Reality

Unlike her sisters, Anne spent several years working as a governess—an experience that deeply informed her fiction. In Victorian England, the governess occupied an ambiguous social position: educated yet economically dependent, refined yet isolated within households.

Anne’s firsthand knowledge of this precarious existence provided the foundation for her first novel:

Agnes Grey (1847)

Published under the pseudonym Acton Bell, the novel tells the story of a young governess struggling with disrespectful employers and unruly children. Unlike the romanticized governess figure later popularized in fiction, Anne’s portrayal is stark and unsentimental.

Agnes endures humiliation, social invisibility, and emotional isolation—but she does not become melodramatic or self-pitying. Instead, she maintains quiet integrity.

What makes Agnes Grey remarkable is its realism. Anne refuses exaggeration. She documents the daily indignities and moral trials of working women with almost documentary restraint.

The Radical Power of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848)

If Agnes Grey established Anne as a serious realist, The Tenant of Wildfell Hallmade her controversial.

The novel centers on Helen Graham, a mysterious woman who arrives at Wildfell Hall with her young son, having fled an abusive, alcoholic husband. At a time when English law gave married women virtually no property rights and little legal protection, Helen’s act of leaving her husband was socially explosive.

Anne does not romanticize her heroine’s suffering. She depicts alcoholism, marital cruelty, psychological manipulation, and the moral decay of privilege with striking candor.

More significantly, Anne frames Helen’s departure not as scandal, but as moral necessity. Helen leaves to protect her son from corruption. This was a direct challenge to Victorian ideals of wifely submission.

Critics at the time were disturbed by the novel’s frankness. Even Charlotte later discouraged its republication, fearing its “coarseness” might damage the Brontë reputation. Yet modern scholars increasingly recognize it as one of the earliest feminist novels in English literature.

I am currently reading this book and I am about half way through. I was intrigued by the concept of a woman at her time leaving an abusive husband and the strength it would take to do something so shocking. So far, it is definitely frank with the description of Arthur’s plunge into debauchery and drunkenness and Helen’s feelings regarding her husband’s downfall. She wishes he would be a stable and loving husband, but you can’t demand things from those incapable. I will be doing a full review when I am finished. Stay tuned.

Pseudonyms and Publication

All three Brontë sisters initially published under male pseudonyms:

• Charlotte as Currer Bell

• Emily as Ellis Bell

• Anne as Acton Bell

This decision was strategic. Female authors in the 1840s were often dismissed as sentimental or frivolous. By adopting ambiguous names, the sisters ensured their work would be judged on literary merit.

In 1847, a single publishing year saw the release of:

• Jane Eyre

• Wuthering Heights

• Agnes Grey

It was an unprecedented literary moment—three sisters producing three radically different novels, each now considered foundational to Victorian fiction.

Anne’s Literary Style: Precision Over Passion

Where Emily is storm and Charlotte is fire, Anne is clear light.

Her prose is controlled, ethically driven, and grounded in psychological observation. She avoids melodrama. Even in scenes of marital abuse in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, Anne resists sensationalism. The horror lies in its plausibility.

Key elements of her style include:

• Moral seriousness without didactic preaching

• Realistic domestic settings

• Exploration of addiction and moral decline

• Advocacy for women’s autonomy

• A belief in spiritual accountability

Anne’s worldview was deeply Christian, but she rejected rigid Calvinist severity. Her writing emphasizes personal responsibility and moral reform rather than predestination.

Illness and Early Death

Tragically, Anne’s life was brief. After the deaths of her siblings Branwell and Emily in 1848, Anne herself fell ill with tuberculosis. Unlike her sister Emily, who refused medical intervention, Anne sought treatment and traveled to the seaside town of Scarborough in hopes the sea air might improve her condition.

She died there on May 28, 1849, at the age of twenty-nine. She is the only Brontë sibling not buried at Haworth.

Her final days, according to Charlotte, were marked by calm acceptance and courage.

Why Anne Brontë Matters Today

Modern literary scholarship has undergone a reassessment of Anne’s importance. Once overshadowed by her sisters, she is now widely regarded as:

• One of the earliest chroniclers of domestic abuse in fiction

• A pioneer in depicting female economic vulnerability

• A realist ahead of her time

• A proto-feminist voice within Victorian literature

Her refusal to soften harsh realities makes her work feel startlingly contemporary. In an era still grappling with gendered power structures and addiction, Anne’s fiction resonates with enduring clarity.

The Quiet Strength of a Literary Legacy

Anne Brontë did not write to dazzle. She wrote to correct falsehood. She wrote to bear witness.

Her novels challenge readers not with gothic excess, but with ethical confrontation. They ask: What does moral courage look like when society condemns it? What does integrity cost?

In the Brontë constellation, Anne is not the brightest star—but she may be the most steady.

For readers seeking Victorian literature grounded in realism, psychological insight, and moral conviction, Anne Brontë remains not merely relevant—but essential.